Doctor Who has a fine comic tradition, one stretching right back to the First Doctor’s debut in the pages of TV Comic in November 1964. Sixteen years later, the first bona fide professional work of writer Alan Moore—who would go on to become one of the most important and iconic comic creators of the modern era—appeared in the pages of the new Doctor Who Weekly magazine.

Moore wrote just five back-up strips for Doctor Who Weekly between June 1980 and October 1981—a grand total of just 28 pages, each (save four) rendered in beautiful monochrome by David Lloyd. Lloyd would later collaborate with Moore on what can be argued as the latter’s first truly great work, V for Vendetta, which first appeared in the pages of the weekly anthology, Warrior, in March 1982.

Although Moore never worked on Doctor Who Weekly’s primary comic strip, his work in the back-up pages represents some of the best of that Golden Age of British comics, a period of around a decade that began with the publication of the short-lived Action in the mid 1970s, and was followed by many others, including Starlord, Tornado, and of course, the legendary SF anthology, 2000AD. While Alan Moore is well known for his contributions to 2000AD, his work on Doctor Who Weekly, while largely overlooked, provides a fascinating look at his early development as a writer.

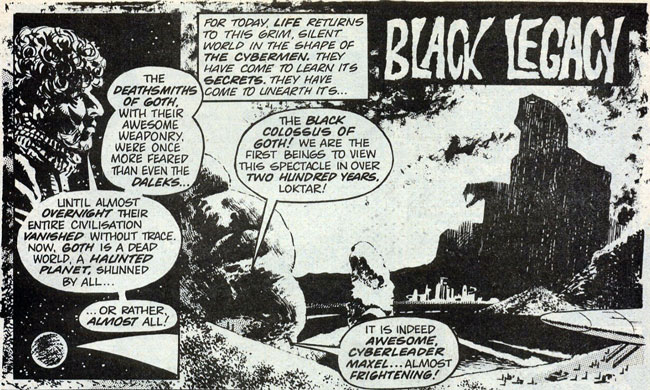

In Black Legacy (4 x 2-page episodes, DWW #35–38, June-July 1980), a group of Cybermen arrive on the planet Goth in search of the ultimate weapon, one crafted by the long-extinct Deathsmiths. One by one, the Cybermen are knocked off by a mysterious something lurking in the shadows, until finally Cyberleader Maxel confronts the menace, only to discover it is the very weapon they were looking for—the Apocalypse Device, a reaper-like figure so powerful that it destroyed its own creators. Trapped on Goth, the Apocalypse Device is determined to escape the planet, but is foiled when the ever-so-slightly paranoid Maxel destroys both himself and his ship. Alas, many months later, another craft arrives on Goth, bringing with it a new group who, like the Cybermen before them, are in search of the ultimate weapon. This time, it is another war-like race, the Sontarans…

Black Legacy is an enjoyable and tightly written story, Moore managing to pace the story perfectly despite the extremely limited two-page format of the episodes. But as far as a Doctor Who story goes… well, if you thought the eponymous villains in Revenge of the Cybermen were a little emotional, wait until you get a load of Maxel’s group. These Cybermen are, essentially, just a bunch of aliens—living ones too, complete with emotions and susceptibility to disease (they even have a medical officer). When Maxel’s subordinate, Loktar, exclaims—with quite some excitement—that the Black Colossus of Goth, a towering monolith, is an awesome and frightening sight, the Maxel reminds him that the Cybermen removed fear when they removed their flesh. This is a great line, but just a couple of panels later the Cyberleader himself is having visions of grandeur, his imagination running wild as he speculates on the amazing power the weapons of the Deathsmiths will grant. The Cybermen having individual names harkens back to The Tenth Planet, but when this is combined with their emotional characters, the fact that they need to sleep (referred to as a “deactivation period”, which feels more like an editorial change than what was written in the script), and various—and surprising—exclamations like Loktar’s cry of “Blood of my ancestors, noooooooo!”, I get the feeling that Moore wrote Black Legacy as a generic SF comic strip, rather than something specifically for Doctor Who Weekly.

But while his lack of Doctor Who knowledge is evident here—and this is not in itself a bad thing, as it is unreasonable to presume that everyone working on a Doctor Who-related project in a professional capacity is a fan—I have to wonder why the editor didn’t step in to make the Cybermen more like, well, Cybermen. In fact, the strip would make a lot more sense if it was the Sontarans who arrived on Goth first, with the Cybermen relegated to just the final panels that close the story. The Sontarans are clones bred for war, so their search for the ultimate weapon makes sense, and while the dialogue would still be a little on the cheesy side, it might sit a little better coming from an angry Sontaran commander than the supposedly cold and logical Cybermen.

That aside, Black Legacy is creepy as hell and a lot fun, with beautiful artwork that packs in so much detail into such short episodes. Moore’s captions are dripping with menace and melodrama, narrating what is essentially a science fiction horror story. A powerful race of aliens creating technology so advanced that it destroys its own creators isn’t particularly original, but in the context of an eight-page back-up, the pulpy quality of the story works very well.

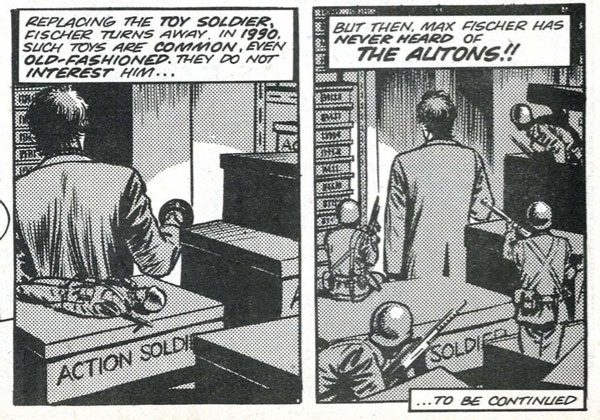

Moore returned to Doctor Who Weekly with Business as Usual, another eight-page back-up split into four two-page episodes (DWW #40–43, July-August 1980). The guest monsters this time are the Autons and the story itself is a somewhat simple mash-up of Spearhead from Space and Terror of the Autons. Our hero, Max Fischer, is special research operative employed by plastics company Interchem who breaks into a rival factory run by, as he discovers, the Nestene Consciousness. After being chased by toy soldiers come to life (reminiscent of Stephen King’s short story Battleground, first published in September 1972 and collected in Night Shift in 1978), Fischer is confronted by Dolman, an Auton replica of the real factory manager, who proceeds to explain—at some length—the entire Nestene invasion plan. Fischer flees in his car, chased by the toy soldiers, but is killed when his vehicle smashes into a tree. With the threat eliminated, an Auton replica of Fischer is created, and the Nestene invasion continues…

Business as Usual has everything you’d expect from an Auton story—plastics factory, a nasty tentacled monstrosity growing in a tank, and regular plastic items (in this case, toys again) coming to life. In contrast to Black Legacy, it seems Moore has been doing some homework, as these are all elements familiar from the two TV appearances of the Autons, right down to the energy spheres falling as meteorites and even a car crashing into a tree (as seen in the Auton’s TV debut, Spearhead from Space, first broadcast in January 1970). But while Business as Usual may be nothing more than an Auton “greatest hits” package, the strip is brisk and simple, and a textbook example of how to plot a completely self-contained story within just eight pages. The ending, though, is a little odd, with the Auton Fischer laying plastic flowers on the real Fischer’s grave. It’s creepy but doesn’t really make much sense, not unless the Nestene Consciousness enjoys gloating over their victories.

In retrospect, Black Legacy and Business as Usual feel like warm-ups to the main act, the sequence of three linked stories which Moore referred to as the “4D War Cycle”. These three four-page stories are unusual in they explore Gallifreyan history and the time of Rassilon, a mysterious period rich with storytelling potential.

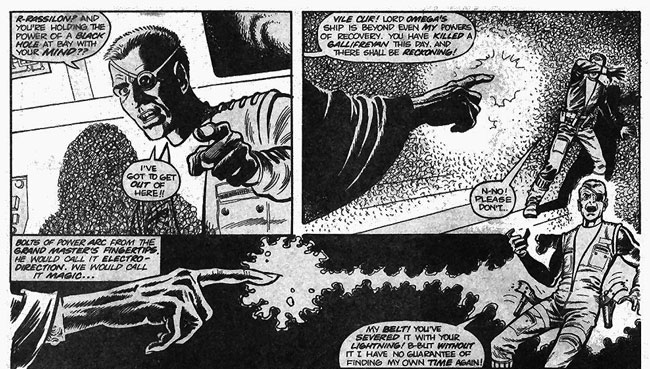

Star Death (DWW #47, December 1980) introduces us to the Lady Jodelex and Lord Griffen, two Gallifreyans overseeing the controlled collapse of the star Qqaba, the remnants of which—a black hole, presumably the Eye of Harmony—will enable the mastery of time and the evolution of Gallifreyans into Time Lords. To set a story right at this pivotal moment in Time Lord history is a risk, but Moore pulls the short story off with aplomb, giving us such exotic creations as the Starbreaker ships and stasis haloes. Seeing the Gallifreyans flying around in spaceships and actually doing something practical is something of a novelty, and here Moore shows a little deeper knowledge of Doctor Who than has been seen previously, with continuity references to both The Three Doctors and The Deadly Assassin. Star Death also introduces a concept which, to modern Doctor Who viewers, sounds rather familiar: the Time War. In this iteration, the Time Lords are—or will be—at war with an enemy from 30,000 years in the future. A mercenary, Fenris the Hell-Bringer, arrives just as Qqaba is about to collapse, sabotaging the stasis haloes of the Starbreaker ships in order to prevent the creation of the Time Lords. But Fenris is defeated by none other than the founder of the Time Lords, Rassilon himself, who Moore casts almost as a sorcerer, shooting “electro-direction” from his fingertips, although not before the ship piloted by legendary stellar engineer Omega is lost. Fenris is sent spinning off into an eternity of torment in the time vortex, his own time travel device picked up by Rassilon and providing the final component he needs to perfect his time travel technology.

Whether it was conceived as a standalone back-up strip, or as part of a larger story, there is nothing in Star Death to indicate that the story would be continued. Reminiscent of the Future Shocks strips from 2000AD—which Moore would write more than fifty of—Star Death is an effective slice of space opera, ably assisted by the superb art by John Stokes. Moore himself later commented that Star Death was one of his favourites of the Doctor Who Weekly strip, with Stokes managing to squeeze in every little detail Moore demanded in his script. There are hints here, too, of something larger; an epic story arc with almost limitless potential, although in this opening instalment the words “Time War” don’t actually feature.

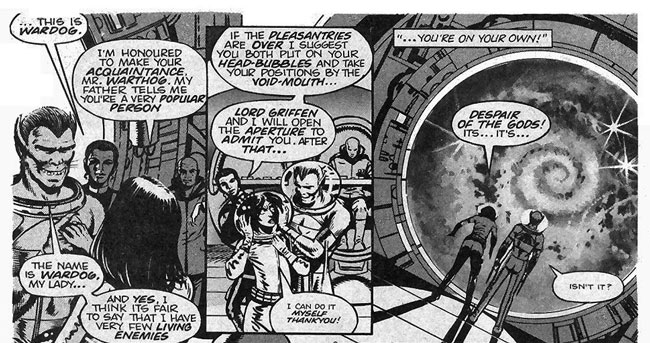

4-D War (DWW #51, April 1981) continues the story twenty years later. Lady Jodelex’s daughter, Rema-Du, leads Wardog—a member of an elite taskforce, the Special Executive—into the time vortex to retrieve Fenris the Hell-Bringer in order to interrogate him about his masters.

The Special Executive are an odd creation, a group of “parahumans” apparently employed by the Time Lords as… well, it’s not abundantly clear in the 4-D War, although we learn more about them in the following story. Rema-Du says that most of the Special Executive give her the creeps, although the only member we meet in this story, Wardog, appears to be a charming werewolf-like warrior whose mind is “different” to others, allowing him to withstand the stresses of the time vortex as he pulls Fenris out. Fenris himself has been broken into splinters, scattered from one end of time to the other—a concept perhaps borrowed from City of Death—and once retrieved is subjected to the Brainfeeler, which extracts the desired information from Fenris’s ruined mind.

Here Moore goes to town on the concept of the Time War, a raging conflict in four dimensions that hasn’t even started yet in Gallifrey’s own timeline. It’s a fascinating concept, obscure and contradictory but, within the parameters of the Doctor Who universe, makes perfect sense. And no sooner has the information been extracted from Fenris than Gallifrey is raided by members of the Order of the Black Sun, revealed to be their enemy, killing Fenris and badly injuring Wardog. Unlike Star Death, 4-D War is clearly the start of something major, with the Time Lords now aware of their enemy and Lord Griffin musing on the nature of the impossible conflict.

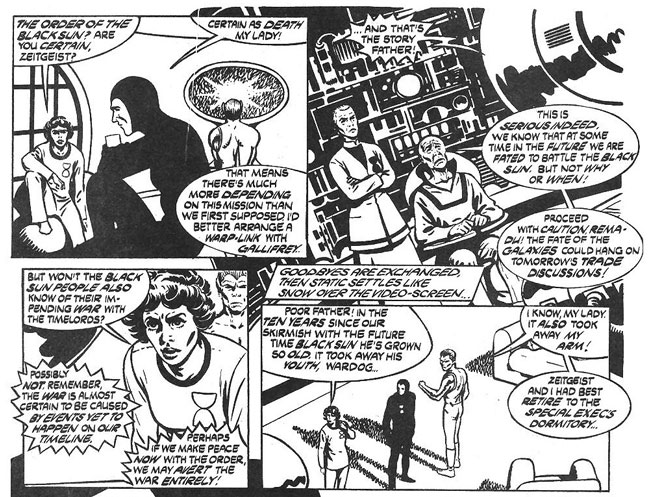

The last of Moore’s strips from Doctor Who Weekly, Black Sun Rising (DWW #57, October 1981), unfortunately falters a little and robs the story arc of its momentum. Rema-Du and the Special Executive are sent to the planet Desrault, where the Time Lords, Sontarans, and an unknown third party (revealed to be the Black Sun at an earlier point in their history, prior to their conflict with the Time Lords) are bidding for… uranium rights?

Yep, uranium rights. Desrault is rich in the element, and according to Lord Griffin, “the fate of galaxies could hang on tomorrow’s trade discussions!” Considering the 4-D War Cycle began with the Time Lords imploding a star to create their own black hole, showing us how powerful they are—even Rassilon’s electro-direction power is referred to as being so advanced it looks like magic—a story hinged around uranium mining rights and trade negotiations seems terribly unambitious. In fact, Black Sun Rising reads like rather old-fashioned science fiction, lacking the imagination and epic scope of the first two instalments.

Having said that, the four-page strip does fulfil two important functions by providing a more detailed introduction to the Special Executive, and showing what might be the first chronological meeting of the Black Sun faction and the Time Lords. In additional to Wardog (now with an artificial arm), three more members of the Special Executive appear—Zeitgeist, skilled in all arts of detection; Cobweb, a telepath; and Millennium, who can accelerate time with her touch. The Special Executive are now clearly a group of Gallifreyan superheroes, complete with catchy names and amazing powers. Moore clearly felt an attachment to them, as he later teamed them up with Captain Britain in Marvel’s anthology series The Daredevils, giving us the tantalizing suggestion that the Marvel and Doctor Who universes are one and the same. But within the context of Doctor Who, I’m not sure the Special Executive are a good fit. It almost feels like Moore is trying to write something—anything!—other than Doctor Who. Which, considering this is the back-up strip, where the rules are a little more flexible, is just fine, although the mix of Doctor Who and superheroes never quite sits right.

As a slow, catch-your-breath episode of a longer story arc, Black Sun Rising would work just fine, but as a standalone four-page strip it’s something of an anti-climax. Moore did intend to continue the story, but he left Doctor Who Weekly along with his mentor Steve Moore, who quit the magazine over a disagreement about the main strip. The Black Sun would never appear again and Moore’s vision of a great four-dimensional Time War faded away. Unfortunately, as it stands, Black Sun Rising is a disappointing end to Moore’s time in the Doctor Who universe, with lackluster dialogue and characterization, and a surprisingly low-key concept.

In the coming decade, Alan Moore would become one of the great writers of the modern comic book era, a creator whose importance to the field cannot be overstated. His five back-up strips for Doctor Who Weekly are an odd but fascinating collection of his early work, and despite their faults, are near-perfect examples of short-form scripting. From pulpy sci-fi to grand space opera, these stories have been relegated largely to curios in Moore’s publication history and have never been collected outside of the pages of Doctor Who Magazine itself and, in the case of the 4D War Cycle, The Daredevils. And that’s a shame, because the Alan Moore Doctor Who Universe is something worth celebrating, not just for what was achieved, but for what might have been.

Adam Christopher is a novelist and comic writer. The author of Made to Kill, Volume 1 in The LA Trilogy, Adam is co-writer of The Shield for Dark Circle Comics and author of the official tie-in novels novels based on the hit CBS television show Elementary.